The conversation with Pham Van Dong took place in the setting of colonial grandeur, the residence of the former French governor of "L'Indochine'". Viet Nam's first prime minister spoke fluent French, which he learned during his years on the French prison island Con Dao off the coast of Southern Viet Nam. Pham Van Dong's long time friend Ho Chi Minh kept an eye on us during the meeting.

A LIFE AT WAR

He certainly looked old and fragile, when he entered the hall through the stately doors of the former residence of the French governor. Prime Minister Pham Van Dong (80) moved very slowly towards us, an aide at each elbow helping him across the marble floor towards the chair - right under the granite head of "Uncle Ho" - his comrade in arms since early youth.

The threadbare suit and worn slippers added to our first impression of a great man, who was well beyond retirement. But it only took a single question on human rights to provoke the fiery stare and a very sharp reply:

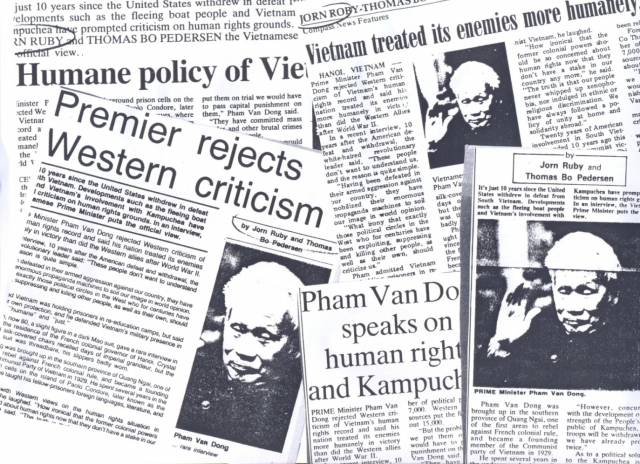

"How dare the West criticize our policies? Look what happened at Nuremberg. The allies executed the Nazi war criminals without hesitation. In my country we have showed leniency even towards the worst of the criminals of the Saigon regime. As soon as we had liberated the South, the killing stopped."

"We even spared the life of the worst criminals. A few of them we keep in jail - also for their own safety. Our people would hang them from the trees, if we let them out. You come here and ask me this kind of questions - why don't you confront your own leaders with their hypocrisy."

"You in the West talk about giving them a fair trial. Let me tell you this: If we put them on trial, there could only be the death sentence for their crimes against the Vietnamese people.

"Now have some tea and think about it, young man," the Prime Minister said, followed by the hearty laugh, customary among many Vietnamese senior leaders.

Kissingers wrath

I wondered if Dong had ever bothered to read Henry Kissinger's memoirs. President Nixon's former Secretary of State and chief negotiator in the peace talks with the Ha Noi leaders had described Dong as "insolent and wily" - no doubt Dong would have taken it as compliment to have exasperated the hot tempered Kissinger.

It was on a cold and grey Ha Noi March morning in 1985, a young official from the foreign ministry had arrived at the government guest house through a drizzling winter rain with an offer no reporter could refuse.

"Ong Pham Van Dong has agreed to see you. Be ready tomorrow at 08:00."

Several months before I had delivered half a dozen written questions via the Vietnamese Embassy in Stockholm to the Prime Minister's office - in the hope that there might be chance. The request had remained unanswered.

Pham Van Dong (left) discussing the battle plans for Dien Bien Phu with president Ho Chi Minh, Communist Party Secretary Truong Chinh and General Vo Nguyen Giap. General Giap is the only one still alive of the founding fathers of the Vietnamese revolution. At the age of 95 he still appears in public from time to time. Giap is fragile but his wry humour is still intact: "It is not difficult to be the great old leader - when you are the only one alive", as he reportedly said to a journalist in 2004 at the 50th anniversary of the battle of Dien Bien Phu.

A founding father

Pham Van Dong had served as Vietnam's prime minister since 1954, more than 30 years - making Fidel Castro look like a junior. Along with Ho Chi Minh, People's Army General Vo Nguyen Giap and party secretary Troung Chinh, Pham Van Dong was a founding member of Viet Nam's Dang Cong San - the communist party.

He had been involved in all major events, since Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam and initiated the rebellion against French colonialism. Pham Van Dong would be a scoop at any time - even more so in 1985, the 10th anniversary of the liberation or fall of the South, depending on who you ask.

Pham Van Dong had seen it all,- and now would he be prepared to talk about it for the first time - to Nha Bao Nuoc Ngoai - foreign reporters? Not quite - it proved. Like other senior Vietnamese leaders he saw no reason to discuss the inner workings of their victory with outsiders.

Why give anything away in a situation, where Viet Nam still felt very much exposed to external threats? Just a few years earlier, in January 1979, Chinese troops had wrecked the Vietnamese border town Lang Son and a great deal of the northern province to 'teach Viet Nam a lesson' in retaliation for Viet Nam's toppling of Pol Pot's Khmer Regime in Cambodia. The year before we had seen ourselves, how Chinese artillery in June 1984 had destroyed some of the few, vital water supply systems in Northern Viet Nam.

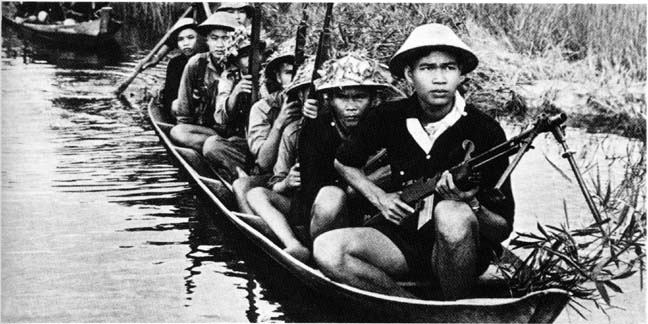

At the same time Viet Nam saw a continous security threat from CIA backed desperado teams which apparently planned to destabilise the country. A very public trial in Ho Chi Minh City a couple of months before had exposed a group of well armed insurgents, who could be traced back to a Southern Vietnamese anti-communist group of exiles in 'Little Saigon' - the city of Garden Grove one hours drive from Los Angeles.

The Vietnamese saw this as a 'Bay of Pigs'-style operation like the ill-fated CIA stunt in Cuba in 1962. In addition The Vietnamese leaders saw a 'diplomatic war' looming in the horizon. All international development assistance to the war torn country had been stopped. All Western embassies were closing down in Ha Noi - except the Swedish one on Kim Ma Street. At a press briefing in Bangkok, a senior US diplomat with Saigon wartime frustrations still ablaze had told us the month before that "the Ha Noi communists were loosing the peace."

Pham Van Dong and the Vietnamese leaders had no plans to give into the huge international pressure, and the Prime Minister readily shared his contempt for Western criticism:

"What irony that those political circles in the West should criticize my country. For centuries the colonial powers have been exploiting, suppressing and killing other peoples - as well as their own. These people who have a long history of enriching themselves at the expense of the poor - they have no legitimacy.

Young man, do you know about the suffering in my country and in many other countries, caused by these Western regimes?"

Pham Van Dong smiled disarmingly.

"How can anyone take the Western powers seriously? The truth is that our people never whipped up xenophobia, nor indulged in religious or ethnic discrimination."

The interview with Prime Minister Pham Van Dong appeared in newspapers in some 30 countries around the world. Viet Nam's legendary Prime Minister did not disclose any war time secrets, but he was a scoop anyway for talking at all.

The Prime Minister patiently listened to other questions on the relations with the Soviet Union, China and the Vietnamese military presence in Cambodia. The replies were polite, but there was not the slightest hesitation in Pham Van Dongs refusal to acknowledge any moral right on part of the West to question the actions of Viet Nam.

However, he did concede that it was not easy for the battle-hardened generation of Viet Nam's senior leaders to cope with the staggering challenges in post-war Viet Nam.

"The many years of war were extremely difficult. Our difficulties are far from over, and it does not make it easier that certain countries try their best to harm us economically and politically. But let me tell you: We are Vietnamese and we did not give up, when facing the strongest military power on earth. And we have no intention to give up now, that we have the unified fatherland, which so many have given their lives for."

A teacher in the tiger cages

Pham Van Dong would not elaborate on his own personal suffering. He would not comment on the numerous stories about his stubborn refusal to give into his torturers during the years in the prison camp on Con Dao Island - where French intelligence held the most important prisoners during the colonial wars.

According to the legends Pham Van Dong had even run an underground school for his fellow prisoners in the infamous "tiger cages", as the cells were called, teaching science, language and literature.

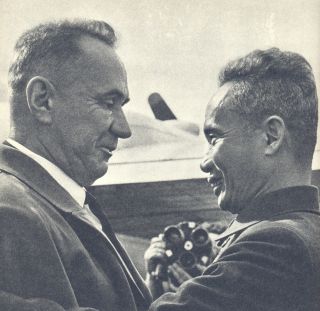

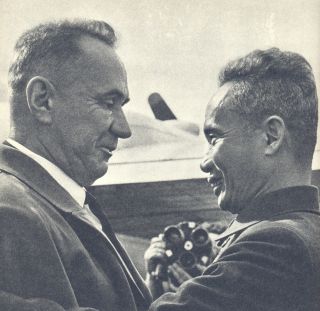

Dong with life time allies: Soviet Premier Alexey Kosygin and Cuba's Fidel Castro.

I had arrived in Ha Noi about a month earlier on my second reporting trip to Viet Nam with press photographer Ole Johnny Sørensen, whose pictures of Vietnamese Agent Orange victims had been printed in numerous newspapers and magazines around the world.

In those days Viet Nam rarely saw sympathetic or impartial Western press coverage - few Western reporters asked to visit, and even fewer were granted a visa. As a result most stories about Viet Nam were filed from Bangkok, Singapore or Hong Kong by Western reporters that picked up most of their leads in the diplomatic community or the vehemently anti-communist communities of overseas Vietnamese.

Our Agent Orange documentation had found its way into some conservative media, and that had given us quite some credit with the rather tight lipped government press center in Ha Noi.

So we had been allowed back for the 10th anniversary of the “liberation of the South” in 1985 along with another Danish reporter Jørn Ruby, who the previous year had antagonized the American Ambassador in Denmark with a series of articles from post-war Viet Nam.

"No friend of America"

The Ambassador had complained to the chief editor, that Jørn “was no friend of America” – having described the obvious double standards in American support to arming Khmer Rouge against the Vietnamese forces in Cambodia. Jørn had simply applied the very standards of impartial and honest journalism that he had been taught during an internship at the Chicago Daily Tribune.

We had spent a month travelling extensively in Vietnam and interviewed dozens of “heroes and heroines” of the American war. It had been a fantastic experience, even though everything was carefully orchestrated by the government press center. We were allowed to see, what they wanted us to see - no more and no less.

Our notebooks and film rolls were full with authorized accounts from the war – but we were still to meet the top echelon of Ha Noi, who we believed could give us a glimpse of the mythical figures that had led the war against the French and the Americans. The ones that had orchestrated the mythical battles of Dien Bien Phu, Khe Sanh, Au Trang and finally the Ho Chi Minh Campaign, which ended 50 years of war.

The meeting with Pham Van Dong became just that - a glimpse of a great warrior on his way to what ever comes after this world. But the secrets were not to be shared with a couple of 'nha bao' from the West.

However, the old Prime Minister lent us one crucial helping hand on our very last day in Ha Noi.

Press photographer Ole Johnny Sørensen had his luggage searched by airport military authorities, minutes before our departure from Viet Nam with loads of excellent material for publication.

"You do not have permission to bring un-developed films about of Viet Nam. You have to leave them here," the officer in charge said with a manner that offered no room for compromise or negotiation.

Ole Johnny looked in despair at a month of work - more than 200 rolls of film slipping away. I shared his desperation. No editor would want a story, however great, if there were no photos. Then I got one my better ideas on that trip. In my handbag I still kept the written invitation from the Prime Minister's office to meet with Pham Van Dong and got it out in a real hurry.

The officer looked like a struck of lightning had hit him and helped Johnny put all the rolls back in his rucksack.

"Xin loi, Anh" - I do apologize, Sir. "I did not mean to offend a visitor of our leader".